The idea of neoliberalism, or new liberalism as it was first called, arose out of a conscious effort to counter prevailing neoclassical ideas, the Keynesian welfare state for example, that themselves were a reaction to the failings of laissez-faire capitalism and the resistance it was creating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The neoliberal economists found a home in an Europe based association called the Mont Pèlerin Society (MPS) in 1947. Founded by its most well known member, the economist F.A. Hayek of the Austrian School. Another infamous member is Milton Friedman of the Chicago School whose quotes are still often banded about by friend and foe.

Though, it must be remembered that not one neoliberal academic defines the cannon of neoliberal thought. Rather as Mirowski tells it, we should recognise them as all part of the neoliberal thought collective.

The core ideas of the collective, and thus neoliberalism, are that the market is the only verifiable method of truth, and that the state’s objective is to create the environment for the latter to flourish free from a Demos whose views would constrain it. Though within the collective, opinion ranged on how to implement the vision: a characteristic of the group.

The corollary to this is that any type of state intervention; neoclassical, socialist or communist; is always doomed to failure as it infringes the knowledge the market produces. For this reason neoliberals, along with hating society in general, particularly have a disliking for Neoclassicalists and Marxists.

By the 1960s the roots of the contemporary neoliberal state emerged in Germany post-World War II (WWII) under the tutelage of a group known as the ordoliberalists.

In government they promoted neoliberal ideas such as privatization, and most notably established the cultural conservative nature of individual economic activity as opposed to collectivist models. In other words they created the first propaganda model to promote neoliberalism.

The majority of the MPS were critical of the ordoliberal compromises with neoclassical policies, due to the condition of post-war Germany, but they understood that they would have to do the same to achieve their goals (Ptak).

Out of this realisation one technique, that Mirowksi calls "double truth precepts", emerged from the MPS. It sought to change the meaning of freedom and destroy Marxism while also promoting confusion among the audience. The penchant of friend and foe to use Friedman quotes, as mentioned above, is one result of this strategy. But a far more insidious development has been how the term neoliberalism has been distored so that our understanding of the developing economic order is also confused.

First, staring in the 1970s the MPS began to use neoliberalism to describe the new economic models that were emerging in Latin America with the imposition of right-wing dictatorships and the ending of of Import Substitution Industrialisation (ISI); a neoclassical idea of state intervention.

By the 2000s the term went global representing all capitalist economic models from Chile to Germany to Japan and South Korea. Countries whose economies were defined as neoliberal due to their adherence to a specific set of ultraliberal polices: pro-market, free trade and anti-statist.

This was further reinforced by the anti-globalist movement who attacked global neoliberalism as an ultraliberal movement from the mid 1990s. A model that represented to them privatisation, deregulation, financialisation and the end of the welfare state for the benefit of the rich at the expense of the poor.

This is highly problematic because the idea that the ultraliberal model is widespread leads to the conclusion that the state has relinquished its role. In fact, the truth is the opposite: the state is stronger then ever, and this is exactly what neoliberalism demands - a strong state that creates the conditions for new markets to emerge.

This is just one mistake that still resonates in the media and academic circles. Below are three other misnomers that have emerged.

First, for example, Harvey (2011) in his A brief history of Neoliberalism, one of the most referenced anti-globalists tomes which I cite him in the next section, notes that neoliberalism only emerged in early 1970s: what he calls the "neoliberal turn".

But this ignores the ordoliberal regimes that ran Germany post-WWII that I mentioned above with their mix of neoclassical and neoliberal policies.

Another example from my own research, which made me question initially the date of the neoliberal turn, is the emergence of special economic zones. Today we recognise them as the neoliberal technology that allowed China to emerge from the late 1970s to become the indiustrial powergouse it is today. But we can date them back to Puerto Rico in the late 1940s. Where they were established by lawyers and business men from the United States (U.S.) looking to create new opportunities in the island's post-war economy.

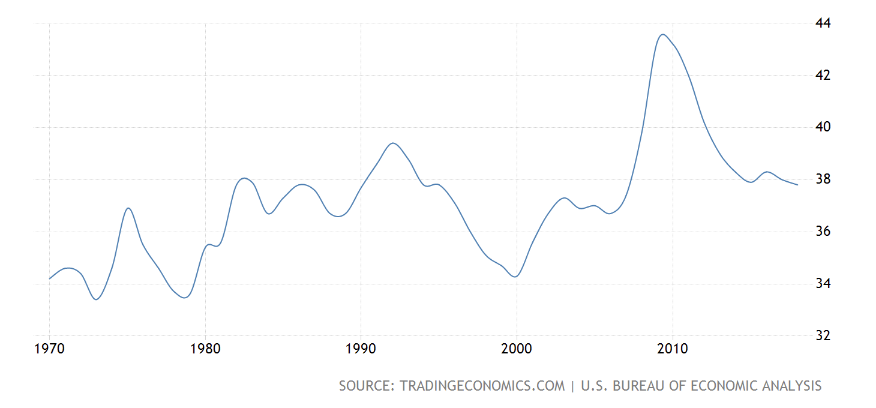

Graph A: United States Government Spending % To GDP 1970-2018.

Graph A: United States Government Spending % To GDP 1970-2018.

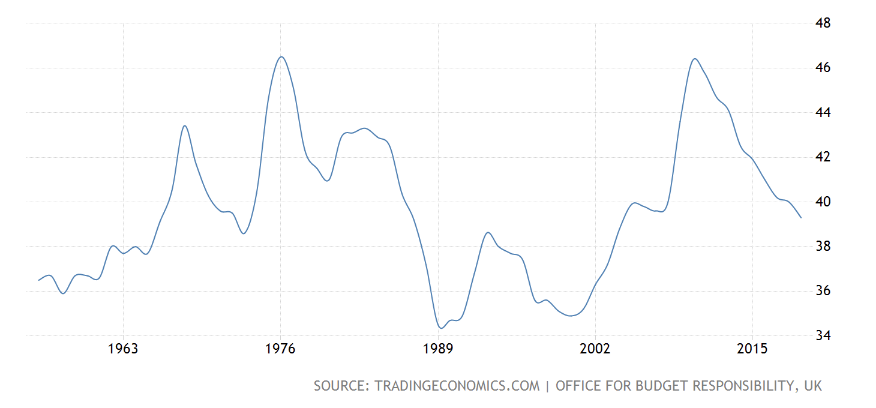

Second, if we look at two nations where the welfare state has been "under attack" since the late 1970s, the U.S. and the United Kingdom (U.K), the numbers are suprising.

Contrary to ultraliberal/anti-globalisation propaganda, the level of state spending in both nations before and after the neoliberal turn remains relatively high and stable between 34% and 46%.

Graph B: United Kingdom Public Sector Total Spending % to GDP 1956-2019.

Graph B: United Kingdom Public Sector Total Spending % to GDP 1956-2019.

In reality the state shifted the spending to the regulation and creation of new markets as opposed to the population though welfare spending.

While, third, the ultraliberal policy of de-regulation is also not as clear cut as it looks. For example, Davies notes that, despite the propoganda, the same Austrian and Chicago School neoliberalis were actually driving a radical restructuring of the legal systems of the US, from the 1970s, and European Union (EU), from late 1990s, to favour a pro-monopoly agenda. Re-regulation, not de-regulation.

So again, what is Neoliberalism?It is a catch all term that covers the capitalist economies that have propagated around the world since the collapse of the Laissez-faire model in the early 20th century.

Much confusion has emerged due to the predominance of an ultraliberal model promoted in certain MPS linked academic groups, the Austrian and Chicago Schools in particular though not exclusively, from the 1970s to explain Latin America's divergence from ISI. By the 1990s this was reinforced by the anti-globalisation movement that promoted the term neoliberal in much the same way as the ultraliberals did, though as a negative to the planet and the majority of the population.

This misconception though is one produced by the neoliberal propaganda machine to seed confusion and obscure the real aims. Which are to form a market economy protected by a strong state whose sole role is to create an environment where the former can operate at full capacity without interference from the Demos. Not a set of policies but rather a philosophy of economic government.

References

Articles & Books

Brennetot, A. (2014) ‘Geohistory of “neoliberalism”: Rethinking the meanings of a malleable and shifting intellectual label’, Cybergeo [Online]. DOI: 10.4000/cybergeo.26324 (Accessed 28 April 2020).

Levitt, K. P. and Seccareccia, M. (2016) ‘“The Political Movement that Dared not Speak its Own Name”: Thoughts on Neoliberalism from a Polanyian Perspective’.

Mirowski, P. (2014) ‘The Political Movement that Dared Not Speak its Own Name: The Neoliberal Thought Collective Under Erasure’, SSRN Electronic Journal [Online]. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2682892 (Accessed 1 May 2020).

Ptak, R. (2009) ‘Neoliberalism in Germany Revisiting the Ordoliberal Foundations of the Social Market Economy’, in Mirowski, P. and Plehwe, D. (eds), The road from Mont Pèlerin: the making of the neoliberal thought collective, Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, pp. 98–138.

Video lectures

Davies, W. (2019) ‘The new digital elites: neoliberalism, technocrats, and their failures’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vdm7E_zZnN4 (Accessed 11 May 2020).

Mirowski, P. (2013) ‘Prof. Philip Mirowski keynote for “Life and Debt” conference’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7ewn29w-9I (Accessed 11 May 2020).

Mirowski, P. (2015) ‘The Terms of Media: Markets’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sw1TNf7YwHA (Accessed 11 May 2020).

Mirowski, P. (2017) ‘Fake News and Fake Experts? Or Should the Experts and the Media Find New Citizens?’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwycuDUWPrY (Accessed 11 May 2020).

Mirowski, P. (2017) ‘Hell is Truth Seen Too Late’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QBB4POvcH18 (Accessed 11 May 2020).

Slobodian, Q. (2019) ‘2019 Chet Mitchell Lecture: Distressed Neoliberalism’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqYBfZsFHNI (Accessed 11 May 2020).

Slobodian, Q. (2020) ‘The coming global recession: building an internationalist response - Webinar recording’, [Online]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LiP5qJhHsjw (Accessed 11 May 2020).